On April 18, 2021, I made my first commit to a project I thought would stay a hobby. Four years and 314 commits later, that side project became OtherSEO. This is what I learned along the way—about SEO, about building tools, and about the problems that are actually worth solving.

Why I Started Building in the First Place

I run a software development company. By 2021, my role had shifted from engineering to business—sales calls, strategy meetings, the usual founder drift. I missed building things.

The initial goal was simple: build an automated system that could collect data from the web at scale. Not for any specific purpose—I just wanted to stay sharp on the engineering side while learning something about information extraction.

What I didn't realize was that this hobby project would become a years-long education in how content actually works on the internet.

The First Lesson: Cost Forces Creativity

Back in 2019, my company had built a news monitoring system for a client. It used early AI to determine whether a page contained an article, then extracted the author, date, content, and headline. This was years before LLMs existed—we were working with transformer models that were still mostly in research phases.

The system worked. It also cost about $0.003 per article collected. That sounds cheap until you're processing thousands of articles daily. Monthly cloud bills became a real problem.

This constraint shaped everything I built afterward. I became obsessed with efficiency—not just making things work, but making them work at scale without burning money on public cloud systems.

I studied how Ahrefs built their business. They bootstrapped to over $100 million in annual revenue by running their own server infrastructure instead of relying on cloud providers. No outside funding. Massive cost advantages. That approach stuck with me.

Lesson: The best tools are built under constraints. When you can't throw money at a problem, you have to actually solve it.

The Pivot I Didn't See Coming

By late 2021, my data collection system was solid. I could crawl websites, extract content, and store it efficiently. But I had no idea what to do with all that data.

Meanwhile, my company was rebranding—shifting from a Hungarian-language website to English-only. We had about 100 articles that needed to move to the new domain. Someone on my team asked the obvious question: "Okay, it's migrated. Now what? Is the SEO actually good?"

I didn't have a good answer. We had content. We had a new site. But I couldn't actually see how the pieces connected—or whether they connected at all.

That question redirected the entire project.

Learning to See What's Invisible

I started adding visualization capabilities to my crawler. Could I map how pages link to each other? Could I see the structure of a website as a network rather than a list?

The first visualizations were rough, but revealing. I could suddenly see patterns that spreadsheets couldn't show: clusters of well-connected content, orphaned pages floating in isolation, bottlenecks where all traffic funneled through a single post.

Around this time, I got interested in knowledge graphs—structured ways to represent relationships between concepts. I was reading everything I could find about how to extract meaning from text and represent it as connected data.

A side project within my side project emerged: monitoring mining and rare earth news for supply chain analysis. I pointed my crawler at five major mining news portals and collected hundreds of thousands of articles. The goal was to map acquisitions, mergers, and infrastructure investments across the industry.

That experiment taught me something important about content at scale: raw data is useless without structure. Knowing that 10,000 articles exist about lithium mining doesn't help anyone. Knowing how those articles relate to each other—what events they describe, what entities they mention, how the story evolves over time—that's valuable.

Lesson: The internet doesn't have an information problem. It has a structure problem. The value isn't in collecting content—it's in revealing relationships.

Then ChatGPT Happened

November 2022 changed everything for everyone in tech. ChatGPT launched, and suddenly the AI capabilities I'd been cobbling together with custom models were available to anyone through a chat interface.

My company had already been experimenting with early generative tools. We'd used Jasper.ai to write about 30 English articles before ChatGPT existed—back when "AI content" still felt experimental and slightly transgressive.

When GPT hit, we made a decision that felt conservative at the time: pause all content investment until the dust settled. We let go of our blogger and waited to see how the landscape would reshape itself.

Three years later, I'm still not sure we've fully figured out the new rules. But one thing became clear quickly: AI made content creation cheaper, which made content architecture more important, not less.

When anyone can produce unlimited content, the bottleneck shifts. The hard problem isn't writing—it's organizing, connecting, and structuring content so it actually performs.

Lesson: Technology shifts don't eliminate problems—they move them. When production gets easy, architecture becomes the differentiator.

The Algorithm That Changed My Approach

By late 2023, I had a clear problem to solve. Our 100-article site was migrated, but the internal linking was a mess. I wanted to generate a task list—something that would tell us: "Article A mentions X. Article B is about X. Link them."

This turned out to be much harder than I expected.

Finding linking opportunities isn't just pattern matching. "Remote work" and "working from home" are the same concept. "Productivity apps" and "task management software" overlap but aren't identical. You need semantic understanding, not just keyword matching.

I spent months implementing and refining algorithms that could identify semantically meaningful connections between articles. The goal was to find opportunities where a link would genuinely help a reader—not just stuff keywords for SEO.

The breakthrough came when I combined this semantic analysis with the visual network mapping I'd built earlier. I could finally see which connections existed and which were missing. The gap analysis became obvious.

Lesson: Internal linking at scale is an algorithmic problem disguised as an editorial one. Humans can't hold 100-node networks in their heads. You need tools that can.

Testing on Ourselves

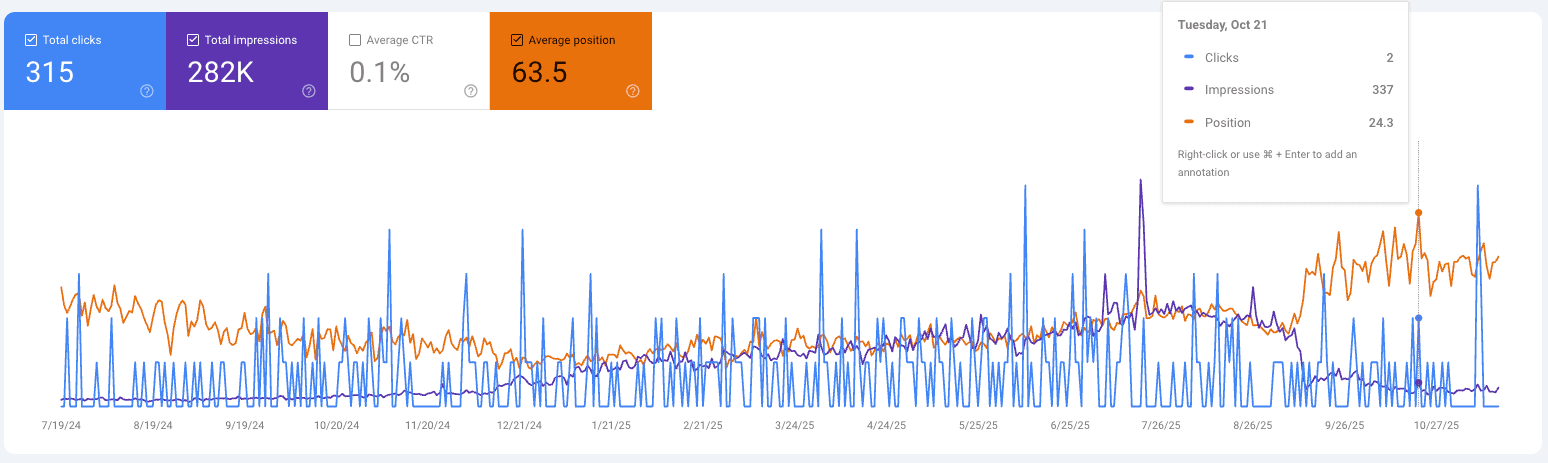

In early 2024, our team applied everything on the new Lexunit company's blog I'd built. We generated the linking opportunity list, grouped articles into semantic clusters, and systematically worked through the recommendations.

We were careful. Every link had to make editorial sense. We didn't over-optimize—the goal was improving user experience, not gaming algorithms. Each article got a handful of new internal links, not dozens.

Then we waited.

The results didn't appear immediately. Google moves slowly. But by the September 2025 core update, the impact was clear: impressions up 180%, average position improved from 63 to 24. We hadn't published significant new content—we'd just connected what we already had.

Lesson: Most sites are sitting on untapped value. The content exists—the connections don't.

What I'm Still Figuring Out

Four years in, I don't have everything solved. Some problems I'm actively working on:

Conversion optimization: Internal linking helps rankings, but how does it affect conversions? Not every link should point everywhere—some paths matter more than others for business outcomes.

AI search optimization: ChatGPT, Claude, Perplexity—they're all becoming search interfaces. The rules for appearing in AI-generated answers aren't the same as traditional SEO. Content architecture probably matters even more, but the specifics are still emerging.

Social signals: How content spreads on social platforms influences how it ranks. The relationship between social distribution and search visibility is underexplored.

I'm building toward a tool that doesn't just fix internal linking, but helps sites become genuinely better—more useful to visitors, more visible to search engines, more effective at converting readers into customers.

Why I'm Sharing This

OtherSEO started as a weekend project to keep my engineering skills sharp. It became something more because the problem it solves—content architecture at scale—turns out to be a genuine gap in the market.

Most SEO tools focus on keywords, backlinks, or technical audits. Content architecture—how your pages relate to each other, how information flows through your site, where the structural gaps exist—gets ignored because it's hard to visualize and harder to fix systematically.

That's the problem I've been solving for four years. Not because someone hired me to, but because I needed the solution myself.

I think the best tools come from that kind of necessity. When you build for yourself first, you can't cheat. The tool either works or it doesn't. No marketing can paper over a bad solution when you're the user.

314 commits later, I think I've built something worth sharing.

See Your Site's Content Architecture

Want to see what your site's content architecture actually looks like? OtherSEO's analysis reveals exactly where your content is disconnected and how to fix it.

What you get:

- Visual site structure map

- AI-powered topic clustering

- Semantic linking opportunities